Call Me by Your Name author André Aciman reflects on an anonymous yet deeply moving letter he received about the novel.

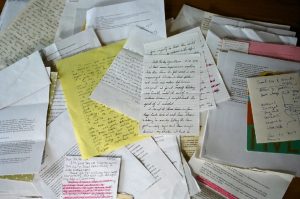

The letter I received ten years ago was unsigned and bore no return address. Clearly its author did not expect, much less want, a reply. A message in a bottle, from no one to no one, that letter still remains the most bizarre form of communication.

IT ASK NOTHING BUT TO BE READ, PROMISES NOTHING BUT TO SHARE A FEW FACTS AND FEELINGS, AND, SEEING THAT IT MUST HAVE BEEN DASHED OFF ON A LINED YELLOW SHEET THAT SEEMED HASTILY TORN AOUT OF A PAD OF PAPER, THE AUTHOR WOULD NOT BE SURPRISED IF, AFTER SKIMMING THROUGH IT, THE RECIPIENT DECIDED TO CRUMPLE AND LOB IT INTO THE CLOSEST DUST BIN

Instead, I kept the letter. I kept it for ten years.

What moved me was not just its sobering matter-of-factness or its hint of downplayed sorrow, but the associations it provoked in my mind. It reminded me of those short, clipped messages to loved ones, written by people about to be shipped off to the death camps who knew they’d never be heard from again. There is a chilling immediacy about their hurriedly scribbled notes that say everything there is to say in the fewest possible words,

THERE WASN’T ENOUGH TIME FOR MORE, NO SMARMY PIETIES, NO HAND-WRINGING, NO TREACLY HUGS AND KISSES BEFORE THE TRAGIC END

The letter is one page long. One page is enough. The handwriting is uneven, perhaps because the author had lost the habit of writing in longhand and preferred the keyboard. But his grammar is perfect. The man knew what he was doing. I assume he was writing the note by hand because he didn’t want traces of it on his laptop, or because he knew he was never going to send it as an email and risk a reply. Now that I think of it, he probably didn’t care if it even reached its recipient, a local Bay Area reporter who had mentioned my novel about two young men who fall in love one summer in Italy in the mid-1980s.

The reporter eventually forwarded it to me, minus its envelope with the postmark. It took no time to see that all the author of the letter was looking for was a chance to blurt out the words he couldn’t dare breathe elsewhere.

My book had spoken to him. His letter spoke to me.

Here it is: dated 16 April 2008

„I came across Mr Aciman’s book during a business trip to the East. Not the kind of book I am usually able to read, so I bought a copy for the flight home. I think I’m glad I did.

You see, I was Elio. I was 18 and my Oliver was 22.

Though the time and place were different, the feelings were remarkably the same. From believing that you’re the only person who has these feelings, to the hole ” he loves me – he loves me not” scenario

Mr Aciman got it right.

I was particularly impressed with the attention he gave to the morning after Elio’s and Oliver’s first encounter. The guilt, the loathing, the fear. I felt it too much. I had to put the book down for a while.

But in the end I was able to finish the book before we landed at SFO. Which was good, because I couldn’t take the book home.

Unlike Elio I was I who married and had children. My Oliver died from AIDS in 1995. And I’m still living a parallel life. My name is not important. His name was Dwight.

“My name is not important,” he writes, almost as an apology for remaining anonymous; yet the author drops quite a number of hints about himself — hints he likely knows will stir his reader’s wistful curiosity to know what made him write the letter in the first place, what he hoped to accomplish, and if writing did indeed help.

What We know about the Writer of the letter?

The letter itself allows us to see that he travels for business. We also sense that he probably lives in the Bay Area and that he travels not infrequently to the East Coast, since, as he writes, he is “back” in the East. And we know one thing more: that he simply needed to come out and tell someone that a man called Dwight had been his lover when the two were young.

The rest is a cloud. We’ll never know more. Writing has served its purpose.

We write, it seems, to reach out to others. Whether we know them or not doesn’t matter. We write to put out into the real world something extremely private within us, to make real what often feels unreal and ever so elusive about ourselves. We write to give a shape to what would otherwise remain amorphous. This is as true about authors as about those who want to correspond with them.

Over the years, many have written to me either after reading or seeing Call Me by Your Name. Some tried to meet me; others confided things they’d never told anyone; and some even managed to call me at the office and, on speaking about my novel, would eventually apologize before bursting out crying. Some were in jail; some were barely adolescents, others old enough to look back at loves seven decades past; and some were priests locked in silence and secrecy.

MANY WERE CLOSETED, OTHERS TOTALLY OUT; SOME WERE WIDOWS WHO FELT A RESURGENCE OF HOPE IF ONLY BY READING ABOUT THE LOVES OF TWO YOUNG MEN CALLED ELIO AND OLIVER IN ITALY; SOME WERE VERY YOUNG GIRLS EAGER TO MEET THEIR LONG-AWAITED OLIVER; AND SOME RECALLED FORMER GAY LOVERS WHOM THEY’D OCCASIONALLY BUMP INTO YEARS LATER BUT WHO’D NEVER ACKNOWLEDGE WHAT THEY’D ONCE SHARED AND DONE TOGETHER WHEN BOTH WERE SCHOOLMATES AND NEITHER WAS MARRIED

All were keenly aware of living a parallel life. In that parallel life things are as they perhaps should be. Elio and Oliver still live together. And no one has secrets there.

Source: Them.us

Pics: Matthew Leifheit.